| LATEST NEWS |

LARGE EDITION PRINTS |

16" EDITION PRINTS |

FOOTBALLER PRINTS |

TRIPLE IMAGE PRINTS |

NAMEPLATE PRINTS |

| PRINT DETAILS & ORDERING | CUSTOMER REVIEWS | THE ARTIST | PRE |

CONTACT DETAILS |

PRE 1825 LOCOMOTIVES

1825 LOCOMOTIVES

PART 3

Part 1: 1802 – 1808

The Locomotives of Richard Trevithick

Part 2: 1812 –1813

Matthew Murray and John Blenkinsop – The rack railways of Middleton Colliery and Kenton & Coxlodge. Chapman's Chain Locomotives

Part 3: 1813 – 1814

William Hedley – The locomotives of Wylam Colliery

Part 4: 1814 – 1816

George Stephenson (1) – The locomotives of Killingworth Colliery from 1814. Chapman/Buddle locomotives for Wallsend and Whitehaven.

Part 5: 1817 – 1825

George Stephenson (2) – The locomotives of Kilmarnock & Troon, Hetton Colliery and 'Locomotion'. Further Chapman/Buddle locomotives.

1813

William Hedley – Wylam Colliery Experimental Locomotive

It had been decided to again experiment with a steam locomotive at Wylam Colliery (Newcastle) so the proprietor, Christopher Blackett, contacted Richard Trevithick but he decline to supply a locomotive as he was to busy.

Blackett then instructed William Hedley the superintendent of Wylam Colliery, to construct one. The idea of using a rack and pinion system was looked at, but to convert the 5 miles, then laid as a plate-way, from Wylam Colliery to the coal staithes on the Tyne, to a rack-rail system would have cost £8,000.

Hedley set out by experiment in 1813 to find out once-and-for-all if sufficient adhesion was available using a smooth wheel on a smooth rail. To do this he constructed a carriage operated by four men, two each side standing on stages suspended from the frame of the carriage. Each man turned a handle, which was connected by a cross shaft to the one on the handle on the other side. A gear was set on this cross shaft which engaged with a gear set on the wheel axle and so turned the wheels and moved the carriage along the plate-way. To make sure that the power was delivered evenly to all wheels at the same time, another gear was placed centrally to engage with the ones on the handle cross-shafts, so coupling the wheels.

He loaded this carriage with known weights ranging from two to six tons then attached more and more loaded coal wagons until the wheels of this man powered carriage slipped round. This experiment proved conclusively that just the friction available from the driving wheels of a locomotive was sufficient to haul a viable train of loaded wagons.

After these successful trials the carriage was converted to an experimental locomotive by mounting a cast iron boiler, with a single straight flue, this was fitted with only one cylinder connected to a flywheel. Was this based on or used parts from the locomotive supplied by Trevithick? This was not a complete success and in Hedley’s own words ‘It went badly, the obvious defect being want of steam’.

It was probably this machine that was seen by George Stephenson and after inspecting it declared he could make a better one himself!

1813

William Hedley – Wylam Colliery Puffing Billy

From the results of the experiments carried out, William Hedley set about designing his second locomotive. Jonathan Foster, who was the engine-wright at Wylam Colliery, carried out its construction.

It differed from previous locomotives by having its two cylinders positioned vertical at the back and outside the boiler, but to keep them hot they were provided with steam jackets. The drive from each cylinder was delivered via ‘grasshopper’ beams running fore-and-aft (the piston rod being connected to one end of the beam via a parallel motion the other end rotating around a fixed bearing). The connecting rods were positioned near the centre of the beam driving down on cranks attached to a cross-shaft running under the boiler to a central cog, as on Blenkinsop’s locomotives, here it drove through intermediate gears to gears fixed to the driving wheel axles, all wheels being driven.

|

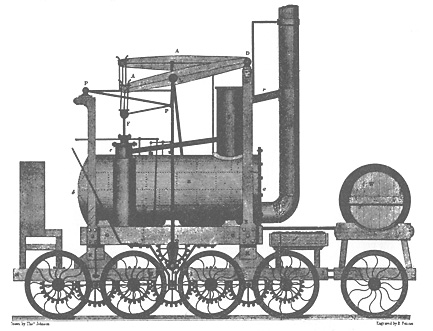

| Drawing showing the locomotives after convertion to an eight wheeler. Taken from Wood's Treatise on Rail Roads 1825. |

The boiler was of wrought iron with a return flue was used to increase the steaming capacity, a fault on the experimental locomotive. The valves were operated by tappets on valve rods hanging from the beams with the exhaust going to a blast pipe in the chimney. A tender was attached to the front (chimney/firebox end) to carry the locomotives essentials for life (water and coal) and from this the fireman could attend the fire. The driver travelled on a footplate at the other end. This locomotive probably incorporated parts from the previous experimental locomotive.

The locomotive started out on four flangeless wheels but the usual problem of broken tram-plates caused it to be altered to an eight wheeler. In 1825 the plate-way was re-laid with stronger edge rails so the locomotive returned to four wheels except this time they were flanged.

|

| Photograph showing Puffing Billy in the last years of its working life. |

The locomotive became known as Puffing Billy and regular worked trains of 50tons at between 4 and 5mph for 48years, although it was extensively modified throughout its working life. The locomotive was lent to the Patent Office Museum, London (the forerunner of the Science Museum) in 1862 and it was only after three years of acrimonious letters that Christopher Blackett agreed to part with it for £40 as he said ‘It could still do useful work’. Happily Puffing Billy has the honour of being the oldest preserved locomotive in the world and is on permanent display in the Science Museum London.

|

| Puffing Billy replica. Photograph © Beamish Open Air Museum. |

A full-size, working replica of Puffing Billy, in its later form, has been built. This was first run in 2006, and can be seen at Beamish Open Air Museum.

1814

William Hedley – Wylam Colliery Wylam Dilly and Lady Mary

Two further locomotives followed Puffing Billy, although being of similar design each succeeding locomotive was an improvement on the last. They were named Wylam Dilly and Lady Mary. These went through the same conversion to eight wheels and then back to four again and like Puffing Billy were extensively modified.

|

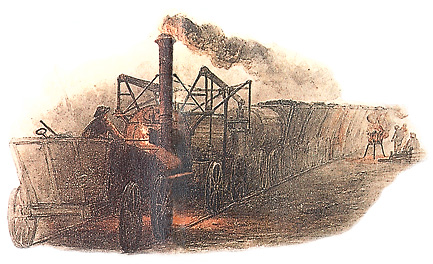

| Illustration of a locomotive at Wylam Colliery. |

Credit for Hedley’s locomotives has also been claimed on behalf of Timothy Hackworth who was, at the time of their construction, the foreman smith at Wylam.

Wylam Dilly is preserved at the Royal Scottish Museum.