| LATEST NEWS |

LARGE EDITION PRINTS |

16" EDITION PRINTS |

FOOTBALLER PRINTS |

TRIPLE IMAGE PRINTS |

NAMEPLATE PRINTS |

| PRINT DETAILS & ORDERING | CUSTOMER REVIEWS | THE ARTIST | PRE |

CONTACT DETAILS |

PRE 1825 LOCOMOTIVES

1825 LOCOMOTIVES

PART 1

Introduction

I have always been interested in the pioneering steam locomotives and because of this I have decided to try and set down, in chronological order, a description of all the locomotives built before 1825. I have added Stockton & Darlington's Locomotion to round off the story.

The text is fairly detailed but not exhaustive; I don't think publishing on the net is the ideal place for this. But I hope to give a good idea of the locomotives and the ideas behind them and perhaps make people want to find out more.

I have only gathered this information from published sources and don't profess to it being my own work. A special mention must go to ‘Early Railway’ published by the Newcomen Society. This contains a series of papers given at the Early Railways Conference in 1988. Especially useful were the papers given by Andy Guy, Jim Rees and Mike Clarke.

Please let me know if you spot any mistakes I have made!

Owing to the amount of information I wish to include I have decide to split it into five parts, each taking as their main theme the following:

Part 1: 1802 – 1808

The Locomotives of Richard Trevithick

Part 2: 1812 –1813

Matthew Murray and John Blenkinsop – The rack railways of Middleton Colliery and Kenton & Coxlodge. Chapman's Chain Locomotives

Part 3: 1813 – 1814

William Hedley – The locomotives of Wylam Colliery

Part 4: 1814 – 1816

George Stephenson (1) – The locomotives of Killingworth Colliery from 1814. Chapman/Buddle locomotives for Wallsend and Whitehaven.

Part 5: 1817 – 1825

George Stephenson (2) – The locomotives of Kilmarnock & Troon, Hetton Colliery and 'Locomotion'. Further Chapman/Buddle locomotives.

Locomotives of other designers are included as they occur in the chronological sequence.

Information about earlier waggonways can be found at the site run by the Waggonway Circle.

Richard Trevithick - Early Experiment

Richard Trevithick was an advocate of the ‘dangerous’ practice of using high-pressure steam. At this time a pressure of only a few pounds per square inch above that of the atmosphere, coupled with a condenser to create the vacuum on the other side of the piston, was employed in the ponderous pumping and mill engines manufactured by Boulton and Watt.

Trevithick used high-pressure to create compact steam engines, which he soon realised could be used to power a self-propelled vehicle. The big advantage of using high-pressure steam was that you could dispense with the bulky condenser.

At the pressure Trevithick favoured, 50psi (pounds per square inch), you could expect four times the power compared with a piston of the same size used in an atmospheric steam engine. Trevithick used a strong cast iron boiler, which was utilised as a structural member. He then placed the cylinder inside it, the great advantage of this being that it kept the cylinder hot and so did not have to waste steam re-heating the cylinder with every power stroke.

In 1803 he turned the exhaust steam up the chimney to create a blast effect. He also replenished his boilers with heated feed water by means of a pump. In 1804 he arranged the valves on his engines to give an early cut-off and so used the steam expansively.

|

Richard Trevithick 1771-1833 advocated the use of high-pressure steam. |

Trevithick made some experimental model self-propelled vehicles incorporating the above ideas. He then made the famous full-sized road vehicle, which made the epic journey up Camborne Hill on Christmas Eve 1801, but the bad state of the roads at this time was not conducive to powered road vehicles.

What Trevithick needed was a smooth surface and this could be found on the industrial tramways and railways. These were being operated by either gravity, ropes or horses. As they were private routes they offered an ideal environment to test a new form of traction, especially as the early ones discharged their exhaust steam straight to the atmosphere, so were noisy and likely to spook the horses on a public highway.

1802

Richard Trevithick – Coalbrookdale Locomotive

The pioneering ironworks at Coalbrookdale was the ideal place to build and try out his first rail locomotive. Another advantage was that it was probably the first railway to be equipped with iron rails.

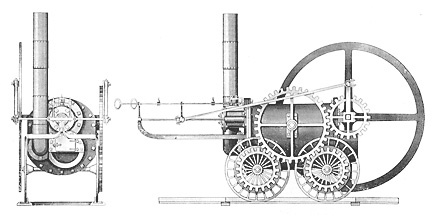

Although records of this locomotive are scarce it is assumed that it was similar to the drawing held by the Science Museum, London, which is shown below. This drawing shows that this locomotive had a cylinder of 4.5 in. diameter and a stroke of 3 ft. and was designed for a tramway with a gauge of 3ft.

|

| Drawing of Trevithick’s Coalbrookdale Locomotive. |

If the locomotive was built as shown in the drawing it would have been very dangerous to fire, on the move as the piston-rod, guide-bars and cross-head are at the same end and directly above the furnace door (perhaps the idea was that the cylinder and flue could be withdrawn from the boiler in one piece for easier cleaning?). This arrangement is most impracticable even on a stationary engine.

|

| The Replica of the Coalbrookdale locomotive at Blist Hills Museum. Picture © Martin Brettle. |

Whatever the layout of the locomotive it did not run for long, as there was an accident followed by an enquiry. The whole episode was hushed-up and the locomotive converted into a stationary engine.

A replica of this locomotive, based on the drawing, has been built and can be seen at Blist Hill Museum, Ironbridge, Shropshire.

1804

Richard Trevithick – Pen-y-Darren Locomotive

Samuel Homfray, the owner of the Pen-y-Darren ironworks near Dowlais, South Wales, contacted Trevithick to see if a steam locomotive could be produced as a practical alternative to horses. This led to Homfray betting Richard Crawshay, ironmaster of neighbouring Cyfarthfa Iron Works, 500 guineas (£525) that a steam locomotive could haul 10 tons of iron over the 9 miles of the Pen-y-Darren tramway to Abercynon where the iron was transferred to barges. The tramway was laid with rails of L-shaped plates, with the flange on the inside, these guided wagons with ordinary non-flanged wheels.

The locomotive designed by Trevithick weighed 5tons, including the water, and it is assumed to have had a horizontal cylinder positioned inside a wrought iron boiler. The piston-rod, guide-bars and cross-head were at the opposite end to the furnace door. This enabling it to be fired while on the move from an attached wagon. The firebox was connected to the chimney via a return ‘U’ shaped flue to get a larger heating surface (i.e. the firebox and chimney were at the same end with the flue running through the boiler to the other end then back to the chimney).

|

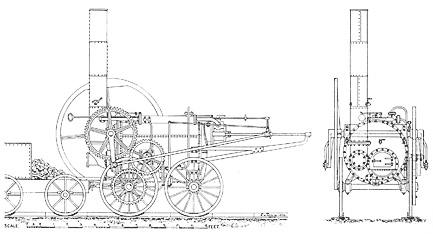

| Drawing of Trevithick’s Pen-y-Darren Locomotive produced by E.W. Twining. |

This was mounted on four wheels, which were attached directly onto the boiler. The single cylinder was 8.25inches in diameter and had a stroke of 4ft. 6 in. Connecting rods ran down either side of the boiler to a crankshaft with a large flywheel on one side, which helped the piston over the dead point, and had gears on the other side, which drove the wheels.

Dr. Dionysius Lardner stated in his book ‘The Steam Engine’ (1840) that the cogs only drove the rear wheels, which were fixed to the axle. This arrangement is shown in the drawing of the locomotive by E.W. Twining (above). The replica of Pen-y-Darren locomotive has been built with both front and rear wheels driven as on the Wylam locomotive (see picture below).

|

| The replica of Trevithick’s Pen-y-Darren Locomotive at Railfest 2004. Picture courtesy of Stephen Dawson's photo site. |

The exhaust steam was directed up the chimney, which Trevithick had realised would draw air through the fire making it burn hotter when it was most needed to create more steam to replace that just used.

Forcing air through a fire to make it hotter was nothing new as metalworkers have used bellows in their furnaces for centuries, so the advantages of this must of been obvious to Trevithick. The surprising thing is that Trevithick did not patent this invention, which later when the exit was restricted became known as the blast-pipe.

The pipe carrying the exhaust steam passed through a jacket in which the feed water circulated thereby heating the water before it was pumped into the boiler.

Homfray won his bet on 21st February 1804 with the locomotive hauling 25tons plus 70 passengers, who had climbed on the wagons to join in the fun, at 5mph and climbing gradients of 1 in 36. Homfray never received the wager. Trevithick wrote that he thought it could haul loads of 40tons. This locomotive proved that a smooth wheel running on smooth rails was a practical proposition.

Unfortunately the weight of the Locomotive, which had no form of suspension, proved too much for the plate-way as it continuously broke the iron rails and so could not be put to permanent use. It was probably converted into a stationary engine.

1805

Richard Trevithick – Gateshead / Wylam Colliery Locomotive

Reports of Richard Trevithick’s Pen-y-Darren locomotive came to the attention of Christopher Blackett the propriety of Wylam Colliery (Newcastle), who ordered a locomotive from Trevithick. This was built at Whinfield’s Foundry, Pipewellgate, Gateshead owned by Trevithick’s agent for the North East John Whinfield. John Steele who had worked on the building of the locomotive at Pen-y-Darren supervised the construction.

|

| Plans of Trevithick’s locomotive for Wylam Colliery held by the Science Museum, London. |

This was designed to be lighter (4.5tons) than the Pen-y-Darren locomotive to try and avoid the problem with broken rails. The cylinder was 7 in. in diameter with a 36 in. stroke.

The drawing shows the locomotive with flanged wheels for use with edge rails. Wylam's waggonway was laid with wooden edge rails to a gauge of 5 ft., unique for the North East. It was re-laid as an iron plate-way, retaining the same gauge, in 1808. This was inspired by a local landowner, William Thomas, who was promoting the idea of a plate-way from Newcastle to Carlisle, with Wylam forming a part.

Trials were carried out at the works, but Blackett did not accept the locomotive and it was converted into a blower for the foundry.

1805

Richard Trevithick – Second Wylam Locomotive?

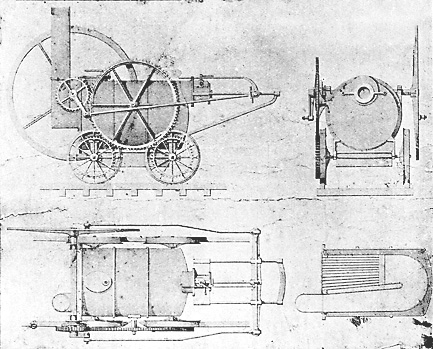

The Science Museum has a plan showing a Trevithick style locomotive similar to the above design but with a shorter boiler and larger wheels. The gearing is 3:2 instead of 2:1 used on the built locomotive. As the gauge of this locomotive is 5 feet, it would imply that it was designed for use at Wylam.

This drawing could have been an alternative design to the one built, but Trevithick himself mentions in January 1805 that he expected to visit Newcastle soon to see some of his ‘travelling engines’. There is also a report that William Chapman had such a locomotive, fitted with roughened wheels as stated in the Trevithick and Vivian Patent of 1802, stored at his ropeworks in Tyneside.

1808

Richard Trevithick – Euston Locomotive Catch-Me-Who-Can

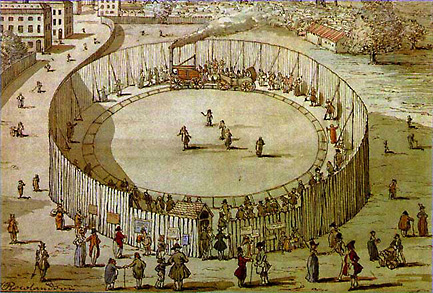

Richard Trevithick seems to have given up the idea of producing steam locomotives until persuaded by his friend, a wealthy Cornish landowner, Davis Giddy to have another go. This locomotive was built to try and get the general public interest in this new form of transport. It was run on a purpose built circular track laid at Euston, London, pulling an open four-wheeled carriage. This took place between 8th July and 18th September 1808 with tickets costing one shilling (5 pence).

|

| Thomas Rowlandson’s watercolour of ‘Catch-Me-Who-Can’ at Euston, London. |

This locomotive was a lot smaller than the others and differed in having the single cylinder positioned vertically, the piston was connected to a transverse beam with the connecting rods working down both sides and were attached directly to the rear wheels. The front wheels being used just to support the front of the locomotive. Using the modern Whyte notation it was a 2-2-0. It is reported to have reached speeds of 12mph.

What happened to this locomotive is a matter of debate. One theory is that it has ended up in the Science Museum, London. A Trevithick engine was discovered on a scrap heap in the goods yard of Hereford station in 1882 and this was rescued by Frances Webb of the London & North Western Railway and taken to the Locomotive Works at Crewe. Here it was reconditioned and presented to the museum in 1896.

|

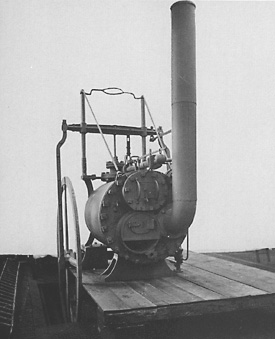

The Trevithick engine rescued by Francis Webb photographed in the Paint Shop at Crew. |

‘Hazeldine & Co of Bridgenorth’ built this engine for Trevithick in 1806. It certainly has a vertical internal cylinder and the general layout looks like the locomotive in the watercolour by Rowlandson but the stationary engines Trevithick supplied were also constructed to this layout. The boiler shell is 56 inches long with a diameter of 45 inches. It has a cylinder of 6.37inches in diameter by 30.5inch stroke. I will duck the issue and leave it up to you to decide if this was used for Catch-Me-Who-Can!